Post Maruti-Suzuki departure, Gurugram needn’t go the Detroit way

Cities and regions always have a variety of factors that come into play to pull them out of anonymity.

For Bengaluru it was favourable weather and a growing pool of engineers graduating from the colleges surrounding it and favourable weather. For New York it was the proximity to the sea and the incoming stream of immigrants. The story of Gurgaon (now Gurugram) was similar. In some ways, the story began with the setting up of the industrial plant by Maruti SuzukiNSE -2.07 % in the city. The recent announcement by the company to relocate out of Gurugram, therefore, presents a unique insight into the causes of rise and fall of cities.

Gurugram’s rise coincided with India’s larger move towards a more open economy from the mid-1980s, which later gathered momentum in early 1990s. A bulk of the city’s industrial base began developing before this period when Maruti Suzuki came into the picture in 1981 — a time when Gurugram was just a village that was struggling to develop into a town. Again, multiple factors played a role in attracting the company to the region, but it became a magnet for other manufacturing firms to shift base as well.

The city’s fortunes changed further in early 1990s with the introduction of market reforms that led to the emergence of India’s outsourcing industry. Multinational companies started looking for office space to house thousands of employees in call centres. Gurugram, which had availability of cheap land in abundance owing to favourable land acquisition policies and development of a robust real estate industry by private players like DLF, proved to be an attractive location for these companies. The proximity to Delhi and the airport also worked in its favour.

The only complexity that ailed the city was an utter lack of basic infrastructureNSE -8.73 %like electricity, water supply and security, among other amenities. Despite these challenges Gurugram has been able to emerge as one of the world’s biggest outsourcing hubs. The agglomeration of firms invested in the basic infrastructural development of the city by bringing in private players that provided power backups due to shortage of electricity, security personnel due to safety concerns, borewells for water scarcity etc.

The benefits of these investments were collectively accrued by the firms as the new business formation that took place in the region attracted diverse talent pool ranging from technical experts to creative minds. The well-educated urban professionals that moved to work for big corporations stimulated the process of urbanisation. This led to the doubling of Gurugram’s population between 2001 and 2011, from 876,000 to more than 1.5 million. Due to the inefficiency of the government, residents’ organisations started pooling money to build parks, fix potholes and to provide for other basic services.

But the private players providing services in the city have created additional problems. For starters, the groundwater level in the city has depleted due to the private borewells and the lack of proper sewage system has polluted nearby rivers and lands. This unplanned urbanised and developed city is now facing the disadvantages of spatial clustering. The excessive clustering of businesses and people has led to overcrowding, increased land prices, and longer commuting timing.

All of these factors make a region unproductive for business and the developmental cycle of a city comes full circle. The causes of agglomeration that had brought about the success of a city in the first place become inimical to its own progress. The relocation of Maruti’s plant is symbolic of such a deagglomeration phase of development for Gurugram.

However, this does not necessarily imply an inevitable demise for the city. New York city, which was an economic centre for America as the shipping route for the country passed through it, managed to find itself on the brink of bankruptcy by the 1970s as commodity shipping moved northwards to a larger canal. But the city quickly reinvented itself into a financial hub as the country moved towards a service-based economy where economic density and human capital are valued more than infrastructural facilities. Another American city, Detroit, which was a manufacturing hub at one point of time, failed to make a similar transformation with the times and perished in the process.

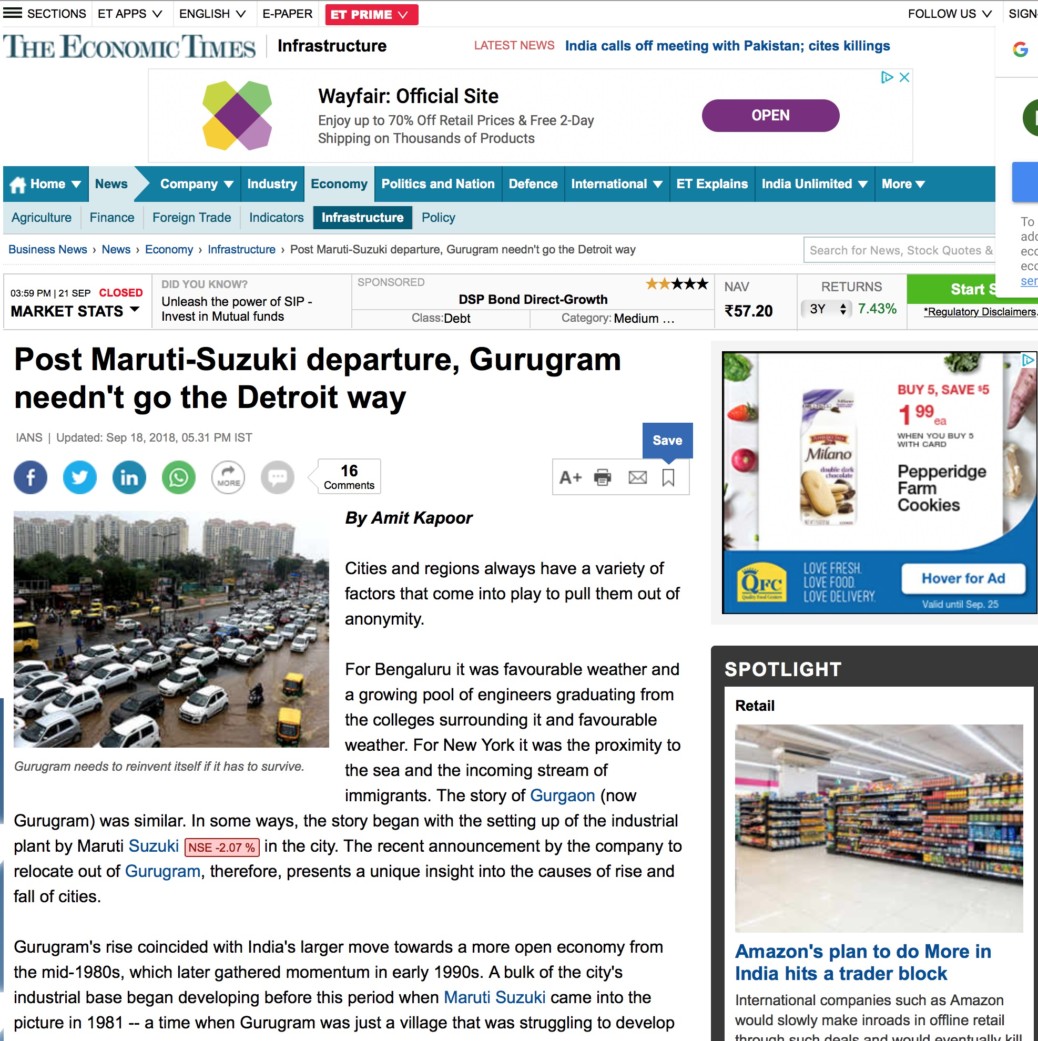

Gurugram needs to reinvent itself if it has to survive. The existence of a thriving services hub in the form of its outsourcing and off-shoring industry works well in its favour. But the government needs to step in to address the issue of resource exploitation that was bound to ensue with higher dependence on private solutions for public services. At the same time, the state government should also utilise this opportunity to build manufacturing clusters in surrounding suburban cities, which can serve the purposes which Gurugram cannot any more. Such opportunities of regional and cluster development should not be missed.

The article was published with Economic Times and Business Standard on September 18, 2018.