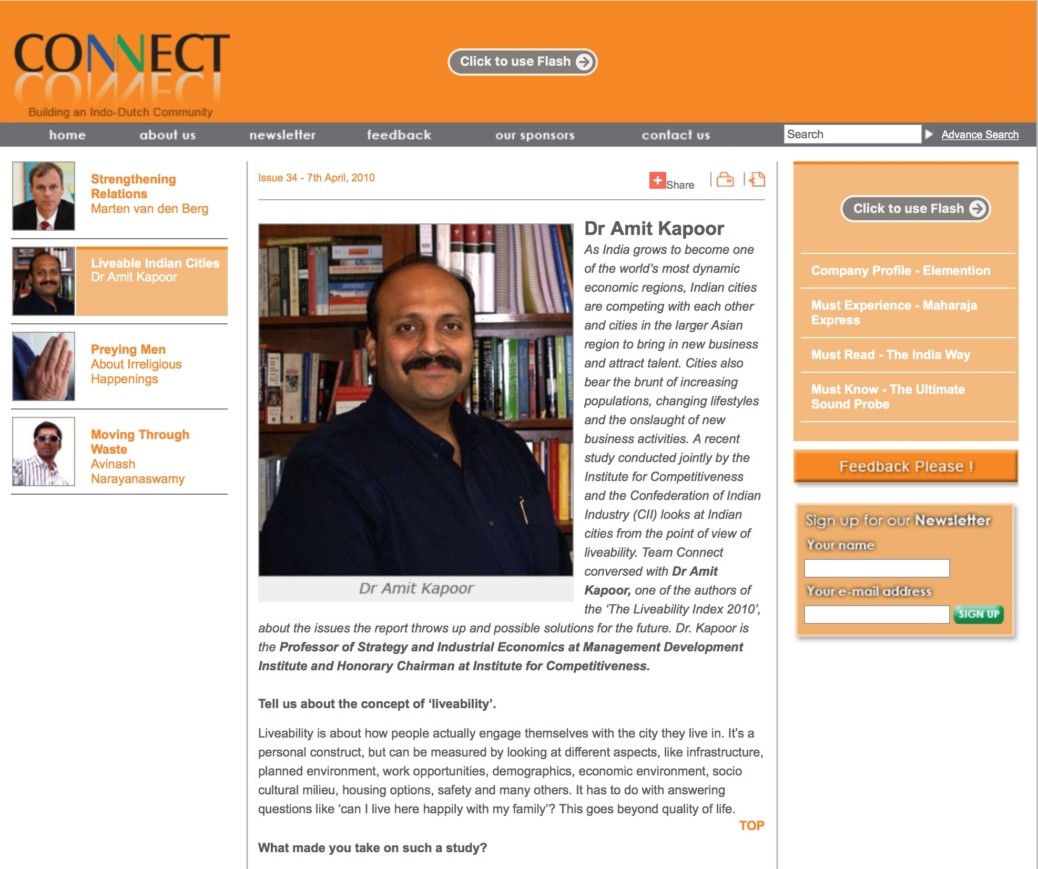

As India grows to become one of the world’s most dynamic economic regions, Indian cities are competing with each other and cities in the larger Asian region to bring in new business and attract talent. Cities also bear the brunt of increasing populations, changing lifestyles and the onslaught of new business activities. A recent study conducted jointly by the Institute for Competitiveness and the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) looks at Indian cities from the point of view of liveability. Team Connect conversed with Dr Amit Kapoor, one of the authors of the ‘The Liveability Index 2010’, about the issues the report throws up and possible solutions for the future. Dr. Kapoor is the Professor of Strategy and Industrial Economics at Management Development Institute and Honorary Chairman at Institute for Competitiveness.

Tell us about the concept of ‘liveability’

How does the report compare with similar international surveys?

On international benchmarks, we’re not doing well. The best in India is ranked at 113th in the world. There is obviously an issue here. We looked at international parameters as well as Indian concerns when we did the study. The relative importance given to the parameters are different in India as compared to say, the US. For instance, in the US, cleanliness may be very important, while in Indian cities, employment opportunities may be far more important.

One major difference is that we’re looking at hard data and not perceptions. Most quality-of-life studies are too dependent on perceptions. If I am born in a city, I like it no matter what and I am biased. We felt we needed to do away with this bias. We looked at hard, published government data. For example, for safety, we looked at the number of accidents, crime incidents reported, etc.

In the West, reports such as these are often used to take decisions about relocating at a personal level. Also, from a foreign investment perspective, does a study like this go on to become a location selector for foreign companies?

The Institute for Competitiveness is involved in projects where urban transportation is being looked at to build integrated mobility and transportation mechanisms. We’re organising the Asia Competitiveness Forum later this month, where we have 50-60 transportation experts coming in to talk about transport and solving problems specific to mobility.

What can city-level governments do with the information from your report? How responsive is the government to suggestions and criticism on urban governance, infrastructure and other issues?

Looking at it from a company’s perspective, a poorly planned urban area means a huge productivity loss. As the total number of hours one spends on the roads increases, one keeps losing productivity. Governments and cities need to look at that.

In India right now, we’re all getting a bit obsessed with IT. Chandigarh, Trivandrum, Pune and many others want to become IT hubs. Why is that necessary? Everyone thinks IT is productive. But productivity can happen in any business. Similarly, there is nothing called a hi-tech industry—every industry can be innovative and hi-tech.

We are being short sighted by not understanding that we can create new centres. Right now, we’re looking at a city that’s doing well and trying to get every industry into that place. There are many examples to look at. Las Vegas created so much prosperity in the middle of the desert. Boston creates immense productivity and value out of being a town focused on education and research. Similarly, the Netherlands became a hub for the flower industry using its logistics expertise. So why can’t we look at things like that?

State governments should look at their cities and look at what they can do with each city in it. Governments have, more and more, started looking at these aspects and chief ministers are increasingly seeing themselves as CEOs. So I see that we are poised for change.