Servicing Next-Gen Agriculture

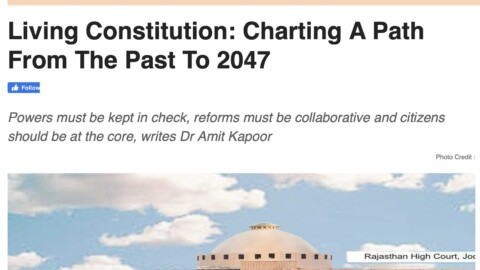

The Economic Survey of India 2024-25 boldly portrays agriculture as the ‘sector of the future’. However, this future may remain bleak unless all the inefficiencies plaguing the sector are identified and addressed through a panoramic lens. While the agriculture sector contributed only around 16% to the country’s gross domestic product in FY 2024 (current prices), it remains the leader in employment, supporting about 46% of the total workforce. On the upside, the real value added per worker in Indian agriculture has grown over the years, albeit slightly. However, its growth has been inconsistent due to constraints from systemic inefficiencies in the sector.

Figure 1: Labour Productivity in Agriculture (1981-82 to 2021-22)

Source: Reserve Bank of India

This can be attributed to hurdles at the pre-harvest and post-harvest stages on the production side of agriculture.

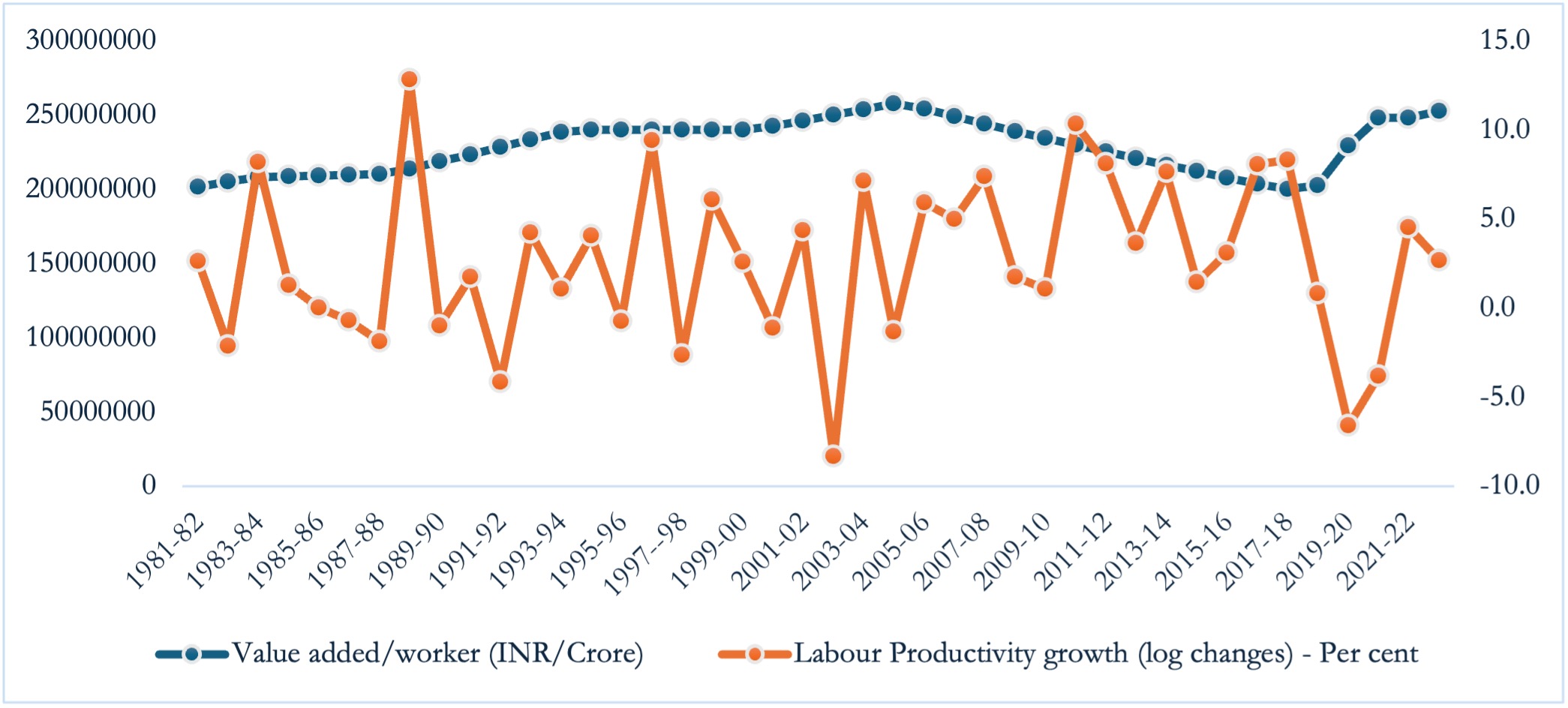

Bottlenecks in the Pre-harvest Stage of Agriculture

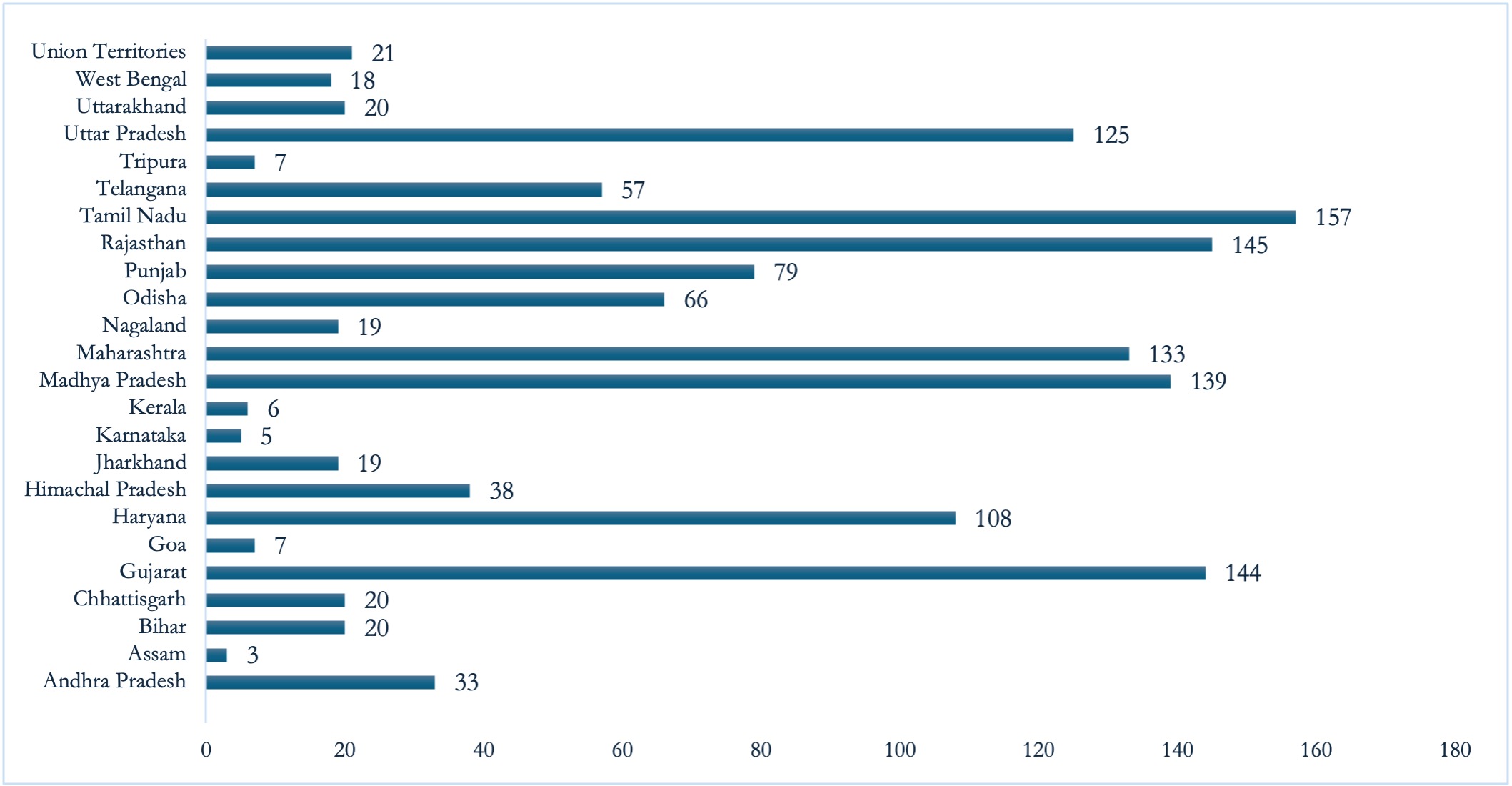

The fact that many farmers still rely on manual labour or traditionally labour-intensive tools for farming due to limited access to affordable machinery keeps labour costs high. In an attempt to resolve this issue, the Government of India has launched the Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanisation, a flagship initiative of the Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare to encourage technology-driven, climate-smart, and precision agriculture practices. Under its realm, custom hiring centres were introduced in 2014-15, as a step towards inclusive farm mechanisation. However, the persistent disparity in the state-wise provision of agricultural machinery as a service on a rental basis seems to be correlated with the accessibility of the state and its intensity of agriculture. As of October 2023, 74,144 custom hiring centres were registered in the country, out of which, more than one-third (32.2%) were concentrated in the agriculturally dominant states of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh; followed by Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu, having almost 30% custom hiring centres. In comparison, custom hiring centres are sparsely located in the northeastern states of India, namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura, highlighting the scope for investment to improve the agricultural efficiency of the region.

Figure 2: State Wise – Custom Hiring Centres in India in 2023

Source: Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanization, Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare

Similarly, as a large part of Indian agriculture is still rain-fed, natural calamities such as droughts or floods can drastically reduce agricultural output. Especially under such circumstances, this implies the sector’s vulnerability to pest infestations and insect attacks, resulting in an increased risk of improper usage of fertilisers and/or pesticides. In addition, most farmers in the country lack access to the latest knowledge, inputs, and agricultural practices to minimise crop damage. These issues reiterate the paucity of investment in agricultural research and development and agricultural extension services.

Nonetheless, the Government of India launched the Soil Health Card Scheme in February 2015 to provide farmers with detailed information about the nutrient status of their soil and recommend balanced proportions of fertiliser use, to improve soil health and productivity. Overall, in 2023-24, 41.12 lakh soil health cards were generated, but they were unevenly spread across the states. More than 50% of the soil health cards were generated for soil samples taken from the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Haryana, Assam, and Rajasthan, indicating unequal state-wise efficiency of the Soil Health Card Scheme in the country.

Figure 3: State Wise – Soil Health Cards (SHCs) Generated in India in 2023-24

Source: Soil Health Dashboard, Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare

The Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanisation also provides financial assistance to custom hiring centres to purchase drones and provide them to farmers on a rental basis. Likewise, financial aid is offered to the farmers, especially the small and marginal, Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe, women, and north-eastern states’ farmers, for individual ownership. It is observed that the states of Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh, which have extensive cultivable land and a high number of small and marginal farmers, also have the highest number of drones that can be used for crop monitoring, precision spraying, and soil health mapping. For instance, the Government of Andhra Pradesh is in the process of deploying Kisan Drones for a variety of uses in the agriculture and allied sector of the state. As one of the first steps, the state government plans to establish 875 drone service centres, at a 40% subsidy offered for their set-up. This could encourage the participation of private players and cooperatives as well.

Figure 4: Total drones distributed under Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanisation

Source: Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanization, Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare

Bottlenecks in the Post-harvest Stage of Agriculture

Despite various policy efforts aimed at modernising Indian agriculture through improved inputs and mechanisation, a major chunk of its output faces post-harvest losses. According to the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, India suffers a loss of about USD 18.5 billion annually, ascribed to post-harvest losses. This can be attributed to inadequate access to fair and transparent markets and storage infrastructure, leading to poor price realisation and wastage.

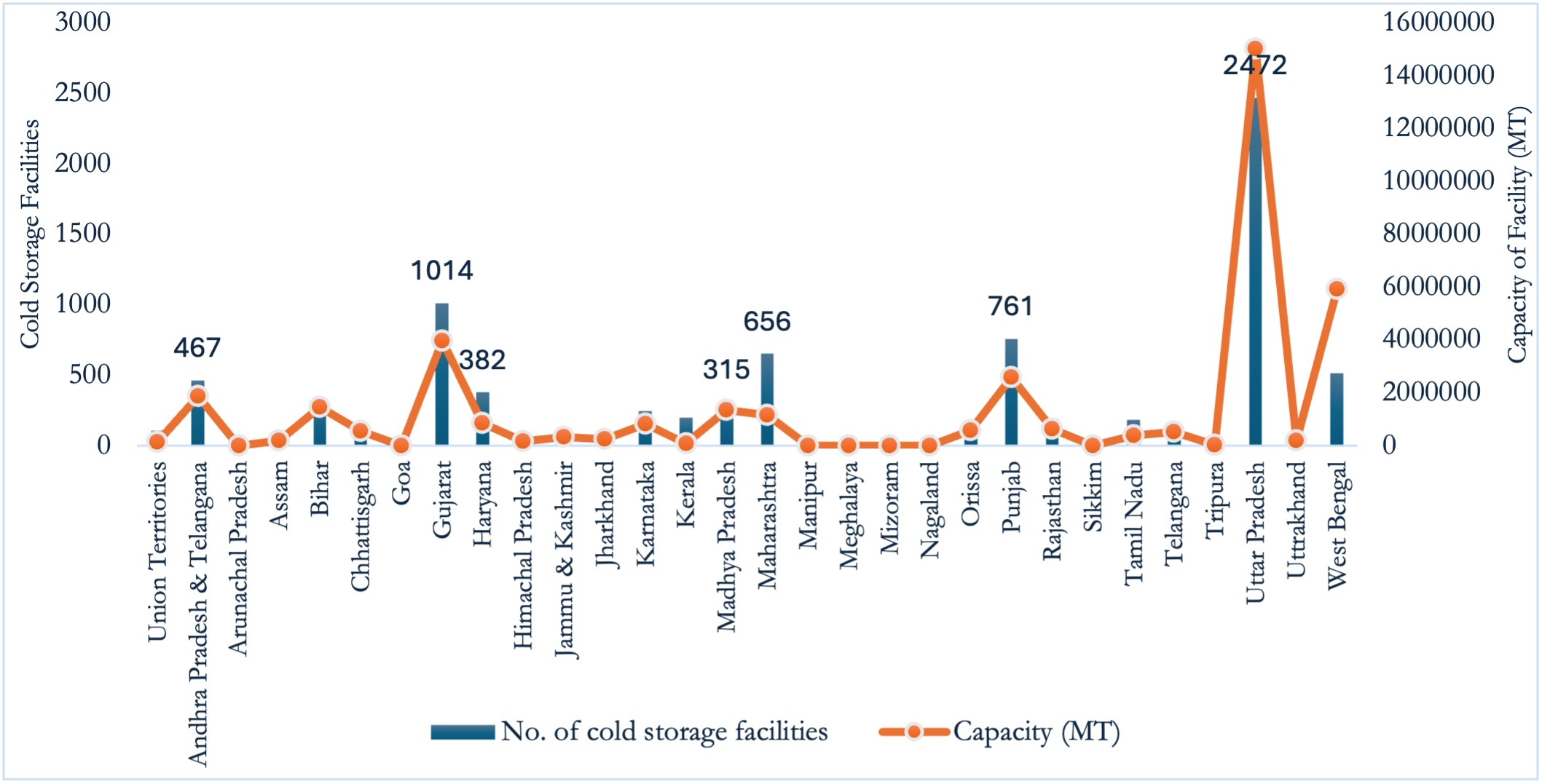

Relatively larger Indian states such as Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu, with a stronger agricultural sector, a more robust network of mandis linked to the Electronic National Agriculture Market system (e-NAM), and cold storage infrastructure, seem more prepared to reap the benefits of better price realisation. Other states, especially those in the northeastern region or categorised as Union Territories, could follow their lead.

Figure 5: Number of mandis integrated with e-NAM platform in 2024

Source: Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare

Note: Union Territories here include Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Jammu & Kashmir and Puducherry

Figure 6: Cold Storage Infrastructure for Agriculture in 2024

Source: Department of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare

Note: Union Territories here include Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep Islands, Puducherry, Delhi, Chandigarh

Up till now, India’s focus in terms of agricultural policies and interventions has largely revolved around two ends of the farming spectrum—inputs and outputs. On one hand, significant emphasis has been laid on the subsidised provision of agricultural inputs such as seeds, fertilisers, credit, and machinery to farmers for decades. On the other hand, efforts have also been directed toward strengthening the market for the trade of agricultural produce. For instance, ensuring price support, procurement, and improving market access through the provision of minimum support prices for crops and the establishment of Agricultural Produce Market Committees across states are some of the measures taken. However, what lies between these two ends of the spectrum is the missing middle of agricultural services that connects traditional farming with modern efficiency.

As India aims to secure its food future amidst climatic, demographic, and economic pressures, agricultural services need a leg up. Offering better and more equitable intermediary support to the farmers via the provision of agricultural services at the pre-harvest and post-harvest stages can help the country’s agriculture sector unlock the next phase of growth. As a starting point, it would enable seamless operations at each step of the agricultural value chain that would improve labour productivity and overall farm efficiency. In other words, optimising the distribution and delivery of agricultural services that facilitate farm mechanisation, soil monitoring, crop and weather advisory, logistics, storage, and other extension support can minimise labour costs and post-harvest losses, and improve soil health, crop yields, and market access. This can eventually enhance farmers’ income-earning capacity. Additionally, a robust ecosystem of agricultural services can reduce the sector’s over-dependence on manual labour and free up human potential for more productive alternate employment. Thus, investing in the upskilling of rural youth as agricultural service providers should also be given due consideration. This would not only create more diversified and gainful employment opportunities in rural areas but also enhance the delivery of agricultural services. Ultimately, with the right training and support, rural youth can become the tech-savvy backbone of a smarter, more sustainable and efficient agricultural future.

At present, the underdevelopment of agricultural services is a critical yet often overlooked factor behind the systemic inefficiencies in Indian agriculture. This acts as both a symptom and a cause of stagnation in the sector. For the modernisation of Indian agriculture and its sustainable growth, its productivity gains must be consistent and inclusive, and the integration of agricultural services can be a game-changer!

he article was published with Open Magazine in the Issue dated June 30, 2025.