The prevailing notion of the ‘triple planetary’ crises encompassing climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss has become outdated in the face of the current complex landscape known as the “poly-crises.” This modern challenge involves the intertwining of climate change, environmental disruptions, widening social inequalities, a global pandemic, and pervasive geopolitical polarization. In the context of India’s ambitious pursuit of rapid economic growth amidst these poly-crises, addressing the climate-development nexus is imperative. The impact of climate change and the depletion of resources holds profound implications for India’s growth trajectory, particularly with a burgeoning population and escalating demands. Amidst these considerations, preserving limited natural resources, especially precious water resources, is a critical priority.

At the recently concluded COP28 in Dubai, countries agreed upon the need to “drive water up the climate agenda”, focusing on freshwater ecosystems, urban water resilience, and water-resilient food systems. Highlighting the gravity of the situation, data from the World Bank underscores that water scarcity could depress GDP growth by 6–14 per cent across significant regions in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. This underscores the inextricable link between climate solutions, development initiatives, and water-related challenges. For India, the imperative to integrate water solutions into its climate and development strategies becomes paramount in navigating the multifaceted challenges posed by the poly-crises.

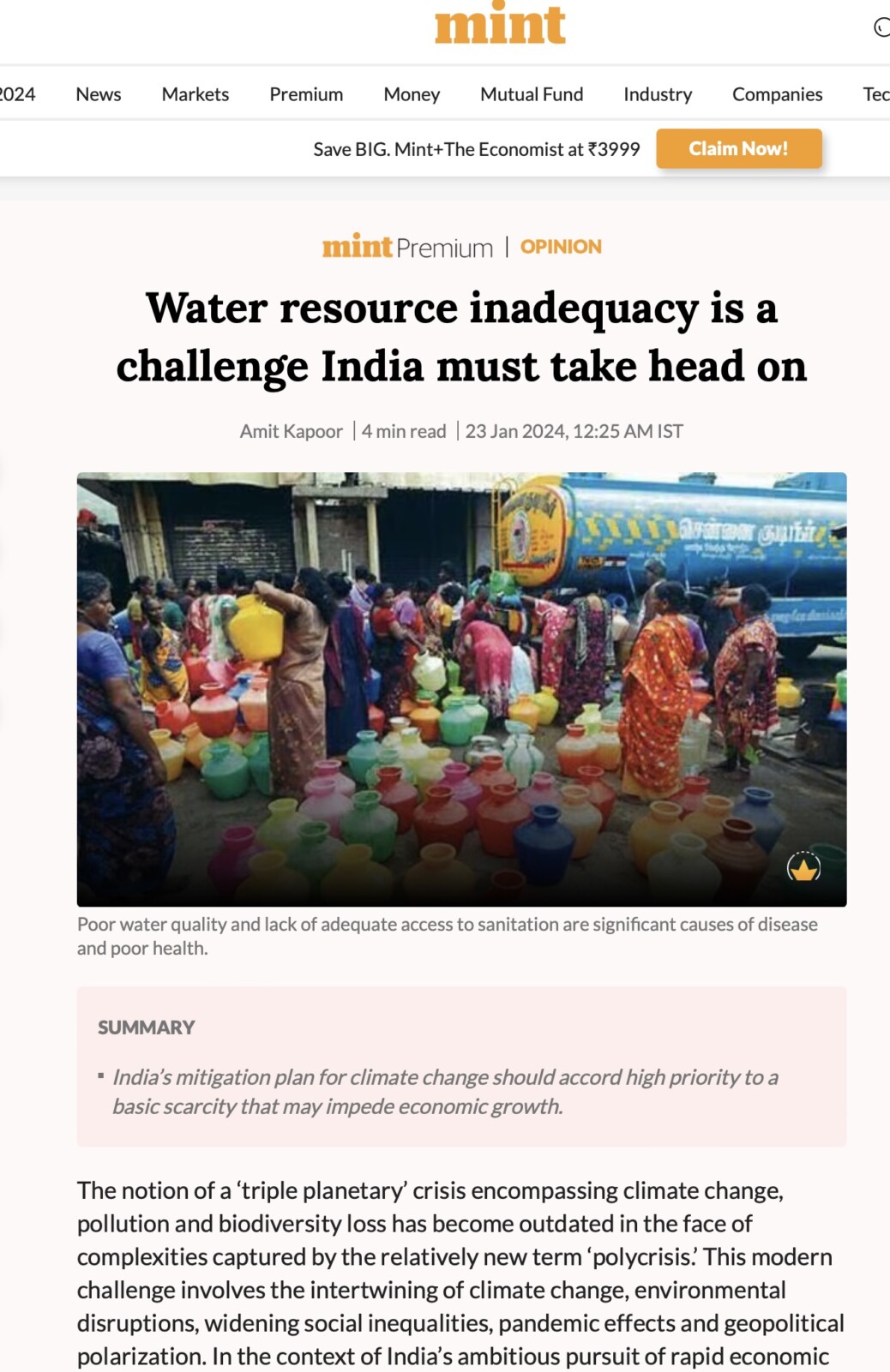

India constitutes 18 percent of the world’s population but has access to only 4 percent of its water resources. This in itself points to an imbalanced demand-supply structure, which has only grown weaker. In the 1960s, the country’s bountiful groundwater resources were critical in driving the green revolution, making it a self-reliant food producer. Today, the country’s water table is rapidly falling, and its aquifers are drying up faster than the rate at which they are being recharged. Declining water tables inevitably lead to a higher cost of pumping and salty irrigation water, resulting in over-abstraction while causing crop and revenue losses for farmers and having long-term consequences for water availability. Poor water quality and lack of adequate access to sanitation are also significant causes of disease and poor health.

This is not news anymore for India. In 2019, the Central Government, with the support of the World Bank, launched Atal Bhujal Yojana- a central sector scheme worth Rs. 6,000 crores aiming to tackle India’s growing groundwater crises.While this is a significant achievement, it still needs to be improved for the country to achieve water security. India can tap into the climate-development nexus by conserving and smartly using its water resources while proactively addressing climate change. With the Indo-Gangetic plain drying up, experts predict that by 2025, North-West India will be subject to severe water stress. Highlighting the water crisis’s economic ramifications, the World Bank projects that certain regions may witness a staggering 11.5% reduction in GDP growth due to water scarcity by 2050.

Additionally, it needs no further elaboration that water insecurity will inevitably impact food and livelihood security across the country. Beyond agriculture, water scarcity will significantly affect India’s quest for sustainable development by having an adverse impact on energy, health, and infrastructure. For instance, in the current structure of India’s power sector, water is a critical component, and a growing economy and industrial boom will intensify water management challenges. Tried and tested development pathways are not only carbon-intensive but also resource-intensive. India is, therefore, at the helm of a significant developmental challenge. How do we overcome this to achieve prosperous and resilient growth?

The policy ecosystem should shift to accommodate shifts in the Earth’s ecosystems. It is high time to remove perverse subsidies, improve water use efficiency, strengthen water governance, and ensure sustainable financing for water infrastructure through appropriate cost recovery. Financing for efficient infrastructure is critical since, currently, large sums are being diverted towards drought relief, both honest and rigged. In 2023 alone, the centre released 7532 Crores to states affected by heavy rains and associated natural disasters.

Better planning and sustainable use of limited water resources should become integral to climate adaptation at all levels. In 2023, Kerala set an example by being the first state in the country to pass a water budget to analyse the distribution and bridge the gaps between demand and supply. While localised planning and community solutions are necessary, more is needed to address issues in the long term; comprehensive planning is vital at the level of the river basin and possible interconnections between river basins. Top-down planning and bottom-up implementation are the way forward. In the context of policy tools, driving water up in India’s National Adaptation Plan is critical.

In the backdrop of extreme weather events, depleting natural resources and drying up of fertile land, India is already in the grip of a severe water crisis, which is and will spiral into a social, political, and economic crisis. We are perhaps only a short time away from adding water stress to the list of “poly-crises” facing the world today. This will undoubtedly exacerbate developmental challenges for India.

(Amit Kapoor is chair, Institute for Competitiveness and lecturer, USATMC, Stanford University. @kautiliya).

The article was published with Mint on January 22, 2024.